With savings, every little bit counts. In our view, one should focus on regular contributions to investment portfolios to build an asset base, in turn allowing investment gains to compound over time and further bolster accumulated assets. In addition to the notion that even small amounts of savings, when invested according to a disciplined strategy, may grow substantially over time, we think the following additional thoughts are important for savers to consider:

- The compounding of returns may add to the proportion of portfolio assets that earlier savings and gains on those savings helped build

- And those compounded gains in absolute dollar terms may become increasingly large with time

- Seemingly small changes in long-term returns can have a relatively outsized impact on the eventual value of an investment portfolio

Listen to this month's Notes from the CIO podcast:

Podcast: Play in new window

Savings are Good…

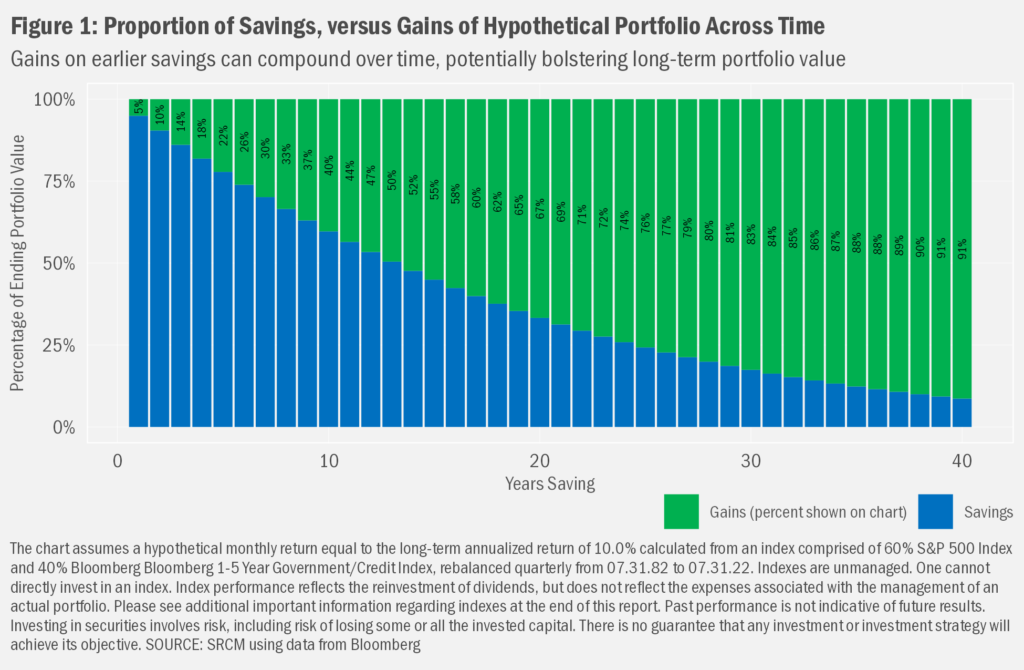

To demonstrate the potential power of a regular savings and investment plan, we created a hypothetical portfolio built using $100 per month in savings that’s invested at an annualized return equal to that achieved by an index reflecting a 60/40 mix of equity and fixed income over the past 40 years. Past performance is not indicative of future performance and one cannot invest in an index, but we think the long-term return of 10.0% achieved by that index sets a reasonable basis for this demonstration. To start the discussion, we show in Figure 1 the proportion of accumulated portfolio value achieved by savings, versus the value achieved by having theoretically invested those savings. After 5 years of savings, the investment gains represent just a bit over a fifth of the portfolio. Not much, but still meaningful. But if one leaves those savings invested, they, too, may grow as returns “compound” over time. After 25 years, those gains represented three-fourths of the portfolio in this hypothetical scenario, a proportion that continued to grow.

…Gains on Savings Even Better

The longer one can save, the longer those gains may compound and the potentially larger the portfolio may become, even as the savings rate might remain relatively small. It’s helpful to think about the extra years of savings as being added at the end of the accumulation phase, rather than at the beginning. And that’s because the later years are when compounding can prove most impactful in terms of absolute dollars. To see how the math works we can break up each month of savings into its own “portfolio”. The first $100 had most of forty years to grow at that near 10% annualized rate, eventually expanding to be worth $4,472. The second month of $100 savings grows at that same rate for 478 months to $4,437. And so on, all the way to month 480, by which time the $48,000 in savings may have grown to a considerably larger sum.

Picking up where we left off in Figure 1, we show the absolute dollar amounts of that hypothetical portfolio built from savings of $100 per month. The substantial boost to long-term growth from compounded returns shows up even more starkly in this view, which includes the hypothetical portfolio value at the end of each year. From a comparatively small $48,000 in total savings, all that compounding of returns in this demonstration results in subsequent gains of more than half a million dollars.

But at What Rate of Return?

We’ve made several critical assumptions so far that may or may not apply to any individual’s personal financial situation. We first assumed a $100 per-month savings rate. That could be more or less affordable for certain folks. We then assumed that savings rate held steady for 40 years. That’s perhaps an even more hard-to-fit assumption, as we would normally assume excess “savable” funds are likely to vary through time, as would the desire to actually stash away those funds in an investment portfolio. We in turn assumed those funds remained invested throughout the time frame at a steady rate of return that almost assuredly won’t be experienced by any individual investor over the next 40 years.

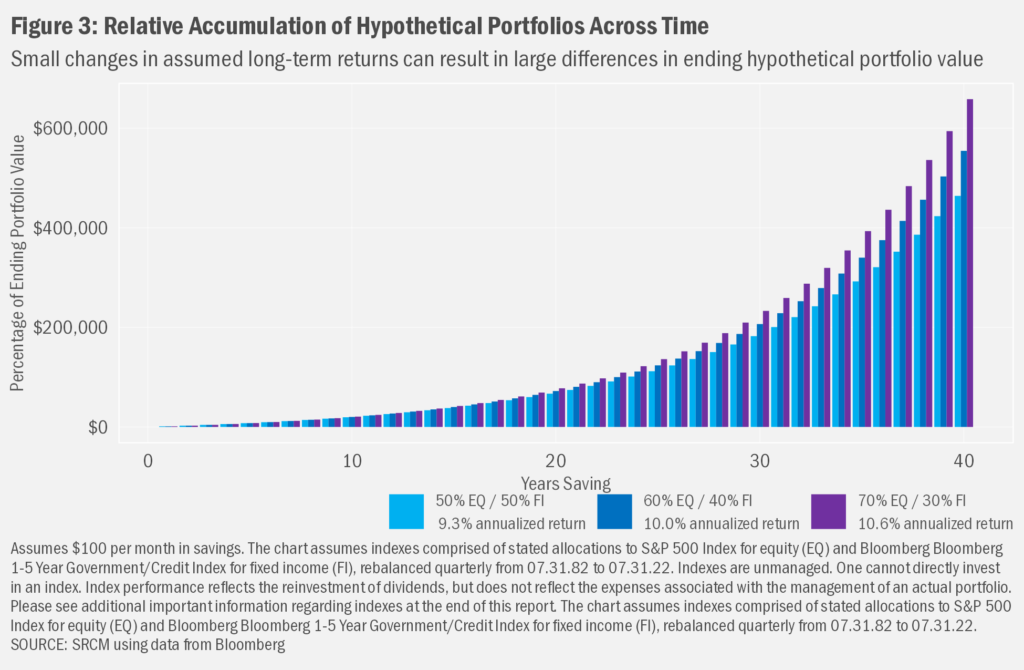

Still, such assumptions allow us to demonstrate the math that we think can be helpful as individuals think about savings for future financial goals. As one can see from the above charts, the more critical variable in the math with regard to the eventual outcome of the savings and investment plan is the rate at which one assumes those savings grow over time. And given the power of compounding, even small differences in the assumed rate of return can have a grand impact on eventual portfolio value. When we calculated data for the charts above, we assume the returns from a “blended” index that combines the returns from an equity index, the S&P 500, and a bond index, the Bloomberg 1-5-Year Government Credit Index, with the former representing 60% of the blend and the latter the remaining 40%. Again, that historical return approximated 10% per year for the past 40 years. Most of that return came from the equity side: the S&P 500 Index posted an annualized return of 12.3% over the past four decades, while that bond index returned a relatively tamer 5.7% per year.

We should highlight that “tamer” bit. Regular readers will know that we often revisit the idea that all investing carries risk and that investing in stocks tends to be risker than investing in bonds. So, the higher return that stocks achieved arrived only via a much more tumultuous path than did the lower return seen by bonds. And that fact is among the reasons we combine stocks and bonds in a portfolio: the bonds can offset the relatively risker stocks, resulting in a lower expected return, but also a lower expected depth and duration of loss. We did so for this very exercise and see that the long-term return of 9.3% for a 50/50 mix of stocks and bonds was a bit lower than that for the 60/40 mix. And the 70/30 mix saw a bit higher return at 10.6%.

Those differences of less than a percentage point might not seem like much, but those seemingly small differences can result in rather large gaps in long-term hypothetical value of an investment portfolio. Figure 3 demonstrates that potential difference. The potential for more sizeable long-term growth of portfolio assets from judiciously taking on incremental risk where one’s financial situation and tolerance for that risk allow is another reason we emphasize that balance of risk and return in our conversations as we seek to assist clients achieve financial goals.

Important Information

Statera Asset Management is a dba of Signature Resources Capital Management, LLC (SRCM), which is a Registered Investment Advisor. Registration of an investment adviser does not imply any specific level of skill or training. The information contained herein has been prepared solely for informational purposes and is not an offer to buy or sell any security or to participate in any trading strategy. Any decision to utilize the services described herein should be made after reviewing such definitive investment management agreement and SRCM’s Form ADV Part 2A and 2Bs and conducting such due diligence as the client deems necessary and consulting the client’s own legal, accounting and tax advisors in order to make an independent determination of the suitability and consequences of SRCM services. Any portfolio with SRCM involves significant risk, including a complete loss of capital. The applicable definitive investment management agreement and Form ADV Part 2 contains a more thorough discussion of risk and conflict, which should be carefully reviewed prior to making any investment decision. Please contact your investment adviser representative to obtain a copy of Form ADV Part 2. All data presented herein is unaudited, subject to revision by SRCM, and is provided solely as a guide to current expectations.

The opinions expressed herein are those of SRCM as of the date of writing and are subject to change. The material is based on SRCM proprietary research and analysis of global markets and investing. The information and/or analysis contained in this material have been compiled, or arrived at, from sources believed to be reliable; however, SRCM does not make any representation as to their accuracy or completeness and does not accept liability for any loss arising from the use hereof. Some internally generated information may be considered theoretical in nature and is subject to inherent limitations associated thereby. Any market exposures referenced may or may not be represented in portfolios of clients of SRCM or its affiliates, and do not represent all securities purchased, sold or recommended for client accounts. The reader should not assume that any investments in market exposures identified or described were or will be profitable. The information in this material may contain projections or other forward-looking statements regarding future events, targets or expectations, and are current as of the date indicated. There is no assurance that such events or targets will be achieved. Thus, potential outcomes may be significantly different. This material is not intended as and should not be used to provide investment advice and is not an offer to sell a security or a solicitation or an offer, or a recommendation, to buy a security. Investors should consult with an advisor to determine the appropriate investment vehicle.

The S&P 500 Index measures the performance of the large-cap segment of the U.S. equity market.

One cannot invest directly in an index. Index performance does not reflect the expenses associated with the management of an actual portfolio. Investing in any investment vehicle carries risk, including the possible loss of principal, and there can be no assurance that any investment strategy will provide positive performance over a period of time. The asset classes and/or investment strategies described in this publication may not be suitable for all investors. Investment decisions should be made based on the investor's specific financial needs and objectives, goals, time horizon, tax liability and risk tolerance.