Many trends suggest progress has been made against inflation, which remains historically elevated across most of the globe. And though mixed in their estimates for how quickly and to what level inflation will fall, survey- and market-based measures for future inflation reflect expectations for a return to more comfortable levels of price change. While we might agree and continue to believe that global efforts to ease upward price pressures ultimately will prove successful, many challenges remain:

- Foremost is the war in Ukraine, inflationary reverberations of which persist around the globe

- Supply-related pressures outside of energy continue to wane, though more slowly than perhaps desired

- Volatile energy markets likely will present ongoing macroeconomic challenges in addition to inflation, with Europe likely particularly stressed

- Higher interest rates may slow regional economies to such an extent that they fall into recession

- Various fiscal measures meant to offset inflation may well limit the near-term effectiveness of monetary policy

Listen to this month's Notes from the CIO podcast:

Podcast: Play in new window

Breaking Away

The U.S. Treasury sells Treasury inflation-protected securities, or TIPS, which offer buyers protection against inflation by adjusting the principal of the bond by the change in the U.S. Consumer Price Index over the life of the bond. Each semiannual coupon is based on that revised principal, and owners receive the higher of the original or the adjusted face value of the bond at maturity. Inflation is generally positive, meaning the principal generally adjusts upward, so TIPS buyers generally accept a lower yield on TIPS, versus a “nominal” bond of similar maturity. Theory suggests that potential buyers will choose the inflation-protected bond only up to the point at which the expected return from TIPS exceed the nominal Treasury yield by an amount sufficient to account for their individual expectations of future inflation and the fact that future inflation is uncertain (i.e., at least their expectations for inflation, probably plus a little bit of a cushion). The difference in those two yields for a given maturity (e.g., 2-year nominal minus 2-year TIPS) is the inflation rate at which the TIPS buyer would breakeven owning either type of bond. That is, inflation “breakeven” rates are indicative of the rate of inflation that would have to be realized over the life of the inflation-protected bond—again, when they consider that future inflation is uncertain (we’ll explain this more in a moment)—for the buyer to be indifferent between having considered the purchase of a normal (“nominal”) Treasury bond or a TIPS.

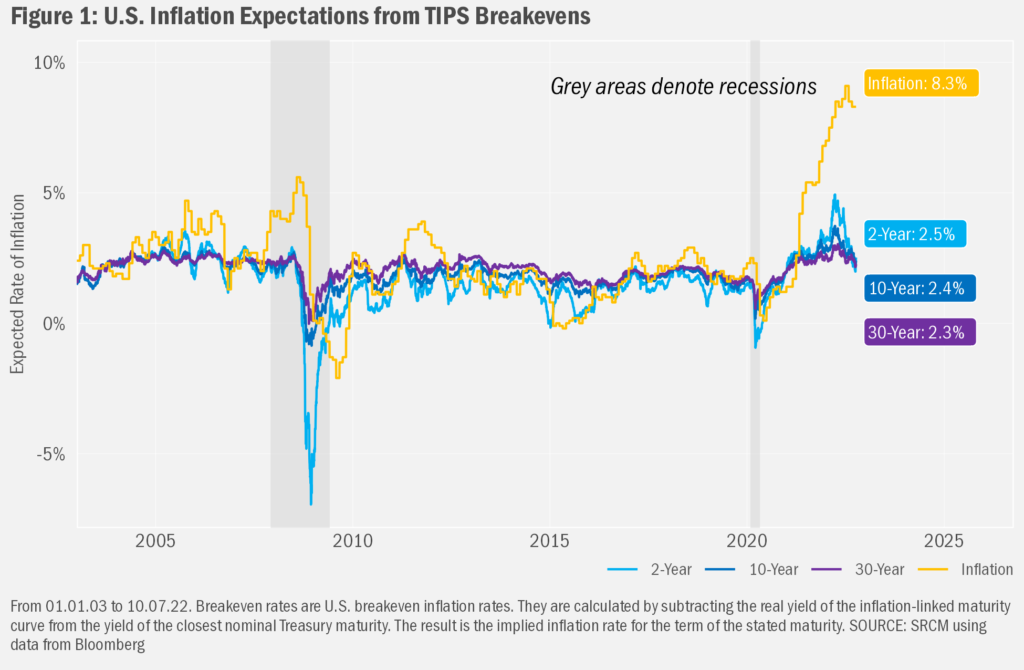

After a surge coming out of the depths of the COVID-19 market crisis, expectations for future inflation continued to rise along with rampant actual inflation. However, as the pace of growth in inflation slowed and then turned flat to negative, investors began to expect prices to grow less quickly in the future. With breakevens now in the mid- to low-2-percent range—well below peak, though still elevated relative to the decade prior to the recent surge—it would seem investors in the aggregate presently surmise that monetary policy ultimately will prove successful.

There are some meaningful caveats to that otherwise favorable take, though. First, theory suggests that among the reasons inflation breakevens may not be entirely accurate depictions solely of investor expectations for future inflation are 1) the thought that the prices of TIPS reflect an inflation premium to account for potential future volatility in inflation, and 2) the fact that the TIPS market is much smaller than the nominal Treasury market the prices of TIPS are thought to be penalized with a discount to reflect the trading challenges presented by lower liquidity (generally higher costs, especially when pressured). More generally, it might be easier to think about TIPS as a form of insurance. Because there generally is a cost to insurance, that cost naturally would be reflected in generally lower yields on TIPS compared to what one might have expected.

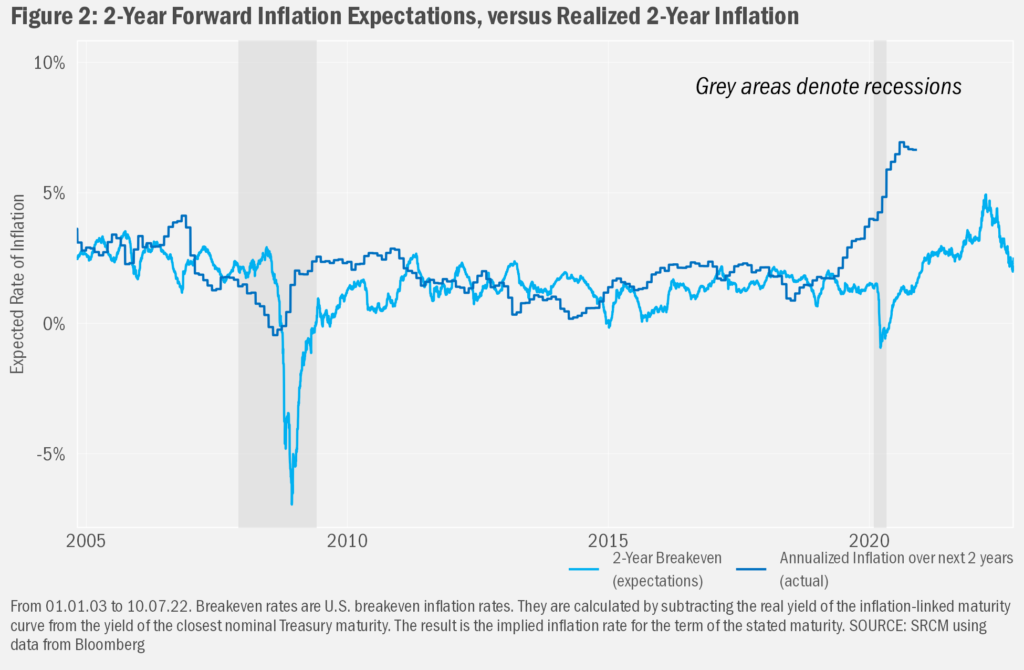

Furthermore, as with most forecasts, expectations do not future results make. In Figure 2 we chart historical breakevens for the next two years of inflation (light blue line) against the actual annualized inflation rate realized over the following two years (dark blue line). Obvious is the fact that the two lines rarely intersect, with inflation expectations often widely off-mark. Larger “misses” tend to be more dramatic around periods of economic uncertainty. For example, investors were slow to believe that inflation would rise back to the Federal Reserve’s target[1] after the Great Financial Crisis of 2008-09, and then were slow to come to terms with the idea that deflation remained a possibility in the early 2010s. And coming out of the COVID crisis, investors clearly misjudged the potential for such dramatic inflation as we have seen over the past year. Potentially happily for them, of course, is the fact that TIPS may have protected them from that unexpectedly higher inflation via the adjustment in principal, versus having chosen a nominal bond (though both types of bonds likely would have been negatively affected by generally rising interest rates).

These data are nonetheless valuable, though, in that among the primary concerns of central bankers around the globe is that higher levels of inflation might become entrenched in public thought, thereby reinforcing inflationary trends as consumers purchase in excess of need or actual desire to avoid having to pay more in the future. Indications that inflation expectations are fading help to ease those fears somewhat.

No Laurels on which to Rest

Positive indications aside, this period of high inflation may well be far from over. And as Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell noted in a recent speech, there may be more pain to come before his team is comfortable that they have succeeded in taming inflation.

War in Ukraine

Perhaps most pressing is the ongoing conflict in Ukraine, which remains at its greatest intensity since the invasion began, while still threatening critical supplies of food and energy. Though fears of a frozen winter due to lack of natural gas have waned, Europe seems at some point quite likely to lose all access to Russian energy supplies, whether by their own choice or by Russian decree. Securing longer-term supplies and establishing natural gas and alternative infrastructure likely will prove costly and take years to totally compensate for failed supplies from Russia. And while grain and other food stuffs continue to flow out of Ukraine, Russia may find earlier agreements no longer tenable.

Supply Chain Disruptions

Off the port of Los Angeles (San Pedro), the Pacific Merchant Shipping Association calculates that the average “dwell” time for containers at the port has dropped from a high of more than eight days last November to just a bit over five days in August. Pre-COVID data suggest a normal time closer to half the latest value, with elevated waits due in part to peak delays in outbound rail traffic and still slow outbound truck traffic. And some of that West Coast port easing comes from a shift in deliveries to still-clogged East Coast ports to avoid what had been pile ups out West. Still, the general progress reflects both the slow unravelling of COVID-related kinks and a slackening in demand. Both can be seen as positive for future inflation, even as the latter is an indication that global growth is stalling. But U.S. and global supply chains remain stressed nonetheless, on account of the war in Ukraine, volatile energy markets and high transportation costs (fuel and otherwise), in addition to delays due to mismatches in levels of imports and exports (delays coming in cause delays going out and vice-versa).

Volatile Energy Markets

Though oil prices remain well below summer peaks, prices remain volatile. And the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) is seeking to limit production in order to prop up prices, already having announced a plan to cut production by 2 million barrels a day. They may not be able to achieve that goal, but these actions may limit further downside in energy prices (and therefore downward pressure on inflation in general). Meantime, gas prices have soared in California and elsewhere in the States due to widespread refining outages, a not-so-friendly reminder that oil doesn’t just flow out of the ground into a barrel and then into our tanks and that disruptions specific to petroleum product supply chains can materially affect prices in the short and medium term.

Heightened Recession Potential

Exorbitant costs and in many places limited availability of fuel, higher interest rates and waning sentiment may slow regional economies to such an extent that they fall into recession. Among developed markets, recessionary pressures seem highest in Europe and the UK. The situation is well different in the U.S., with employment robust and growth still well in the positive domain. But a recession is not out of the realm of possibility this year or next. As we’ve discussed in prior commentaries, the fact that the stock market remains well off peak highs reached at the beginning of 2022, while longer-term bond yields reflect an eventual easing of rates on account of slowing growth, give some peace of mind with regard to potential further downside.

Meantime, politicians may feel the need to offset inflation and the negative influence of higher interest rates through supportive fiscal measures. But most measures we’ve seen—borne as much of political expediency as they are of a desire to support those truly in need—are likely to prove temporary and likely will serve only to stimy progress against inflation, not provide any durable impact.

What’s Not Yet Known?

Of course, forecasts (including those we just offered) are generally unreliable, so who knows what’s to come. While it’s hard to be sure to what extent markets discount the range of current “normal” and “not normal” risks, we do have the sense that they minimally express moderate expectations of a meaningful slowdown in macroeconomic activity and even recessions in many regional economies, the United States included. The greatest uncertainties, in our view, relate to the war in Ukraine. With no end in sight, and hostilities on the rise amidst more ominous threats of existential escalation, the near-, medium and long-term impacts of war remain highly uncertain and likely will continue to press investible markets.

As we head into the final quarter of 2022, we want to remind readers that now is as good a time as ever to reach out to an advisor to discuss implications of decisions required prior to year-end. And we are of course always available to review matters discussed in this month’s and other commentaries, in particular as they relate to any changes in preference and tolerance for exposure to market risk.

Important Information

Signature Resources Capital Management, LLC (SRCM) is a Registered Investment Advisor. Registration of an investment adviser does not imply any specific level of skill or training. The information contained herein has been prepared solely for informational purposes. It is not intended as and should not be used to provide investment advice and is not an offer to buy or sell any security or to participate in any trading strategy. Any decision to utilize the services described herein should be made after reviewing such definitive investment management agreement and SRCM’s Form ADV Part 2A and 2Bs and conducting such due diligence as the client deems necessary and consulting the client’s own legal, accounting and tax advisors in order to make an independent determination of the suitability and consequences of SRCM services. Any portfolio with SRCM involves significant risk, including a complete loss of capital. The applicable definitive investment management agreement and Form ADV Part 2 contains a more thorough discussion of risk and conflict, which should be carefully reviewed prior to making any investment decision. All data presented herein is unaudited, subject to revision by SRCM, and is provided solely as a guide to current expectations.

The opinions expressed herein are those of SRCM as of the date of writing and are subject to change. The material is based on SRCM proprietary research and analysis of global markets and investing. The information and/or analysis contained in this material have been compiled, or arrived at, from sources believed to be reliable; however, SRCM does not make any representation as to their accuracy or completeness and does not accept liability for any loss arising from the use hereof. Some internally generated information may be considered theoretical in nature and is subject to inherent limitations associated thereby. Any market exposures referenced may or may not be represented in portfolios of clients of SRCM or its affiliates, and do not represent all securities purchased, sold or recommended for client accounts. The reader should not assume that any investments in market exposures identified or described were or will be profitable. The information in this material may contain projections or other forward-looking statements regarding future events, targets or expectations, and are current as of the date indicated. There is no assurance that such events or targets will be achieved. Thus, potential outcomes may be significantly different. This material is not intended as and should not be used to provide investment advice and is not an offer to sell a security or a solicitation or an offer, or a recommendation, to buy a security. Investors should consult with an advisor to determine the appropriate investment vehicle.

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) is a measure of the average change over time in the prices paid by urban consumers for a market basket of consumer goods and services. Indexes are available for the U.S. and various geographic areas.

The PCE price index reflects changes in the prices of goods and services purchased by consumers in the United States.

One cannot invest directly in an index. Index performance does not reflect the expenses associated with the management of an actual portfolio. Investing in any investment vehicle carries risk, including the possible loss of principal, and there can be no assurance that any investment strategy will provide positive performance over a period of time. The asset classes and/or investment strategies described in this publication may not be suitable for all investors. Investment decisions should be made based on the investor's specific financial needs and objectives, goals, time horizon, tax liability and risk tolerance.

[1] It’s important to note here that, while the Consumer Price Index (CPI) tends to be the more talked about inflation rate, and one that seems to more closely track how consumers experience inflation (with many caveats that are challenging to delineate on the limited space these pages provide, such as the manner in which housing inflation is incorporated into the math), the Federal Reserve prefers to use the “core” Personal Consumption Expenditures Index (PCE) to track inflation. Perhaps the most obvious difference between the two approaches is that the latter excludes changes in food and energy prices. Those exclusions have resulted in periodically wide differences in the two series; recent data show a wide gap as a result of price volatility in food and energy.